Working Draft

This site is currently a working draft of the ITABoK 3.0. In the meantime please utilize the current ITABoK version 2.0

Innovation and Disruption

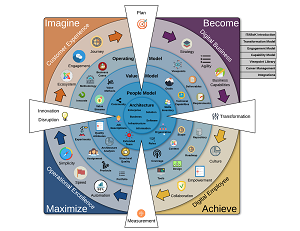

Both Innovation and Disruption are terms used in the ITABoK to describe a set of concepts which relate to the how both Innovation and Disruption form a part of an overall Architecture capability.

The “Innovation Mandate” is clear and well known, but many organizations still continue to struggle, both to formalize a managed framework and also to move the dial from run the organization costs to move those costs to managed innovation projects and programs.

True disruptive innovation that drives growth and transformation has been the holy grail of business for quite some time, and prescriptive guidance in this area is well covered in the literature (e.g., Christensen’s “Innovator’s Dilemma”, Drucker’s “Innovation and Entrepreneurship”, etc.) This being said, disruptive companies are aware of (and utilizing) many innovation best practices falter and fail all the time, underscoring that there is no real silver bullet for success in a competitive business world. This dynamic has only accelerated in the digital age, with upstarts rising faster, with their ability to try new innovation methods at low and risk that has been previously possible.

Areas that most organization fail to realize the true benefits of innovation to drive market and digital innovation include;

- Hard to create innovation engines traditional operating models and structures

- Misalignment of incentives and focus

- Incremental innovations culture that fits with BAU

- Complexity in identifying valuable innovations

- Innovations usually executed in new business domains, not in the mainstream

Description

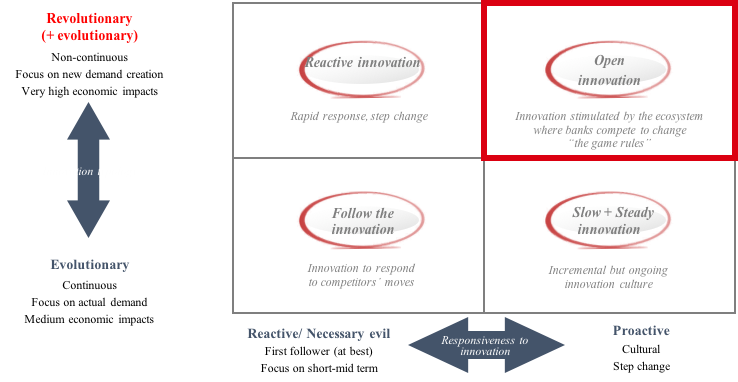

IT is taking an increased role as organizations transition to “Digital Businesses”, but it needs to do more to counter resistance to change

- Moving forward, IT needs to complement and leverage investments in efficiency-type innovations (e.g. productivity), to drive more transformative, disruptive types of innovation (e.g., new sourcing models, new markets, new and different products) and stay ahead of the competition.

- For this to be successful, IT and business leadership need to work together even more closely than before to build IT capabilities that drive growth and transformation-type innovation in the context of current organizational structures, leadership, people, process, culture and technology portfolios.

- Of course, this is easier said than done. A number of factors (including the current state context mentioned above) will dictate: (a) An organization’s readiness for this type of change (b) The amount of resistance thought leaders will face when pursuing this type of transition (c) Where and how fast it can happen.

Innovation Management

To be successful in innovation management, any company should establish the corporate culture that motivates project teams to maximize potential business benefits of project success and minimize potential negative impacts of project failure. Managing innovation is inherently risky. Many uncertainties about future events arise from both internal and external sources. Active Risk Management (ARM) recognizes that these uncertainties can be either threats or opportunities, and ARM endeavors to position the enterprise so that it enjoys most of the benefits of opportunity while avoiding most of the pain associated with threats. This new culture has several differences compared with the traditional approach:

Traditional Approach

- Time to market Every project must succeed Failed projects = failed project managers Risk avoidance

Innovative Approach

- Time to profit Most projects should fail Failed projects = valuable corporate learning Active Risk Management

- TIME TO MARKET VS. TIME TO PROFIT

- The fad called “time to market” has long ago been thoroughly discredited as a means of managing risk. Too many companies have won too many time-to-market races only to discover that somebody else did the job better, though perhaps more slowly, and is enjoying market dominance. An example is Sony’s Betamax video recorder. Sony was first to market with a technologically superior product. In its haste to get a product out the door, however, Sony overlooked several “other things.” JVC Corporation, proceeding more deliberately, was late to market with a technically inferior product, VHS. JVC, however, identified the opportunity to put a feature length movie on a single cassette and the need for a global manufacturing and distribution network to reach potential customers. JVC became the sole purveyor of video recording technology to the mass market for a quarter of a century.

- It was no accident. JVC accepted difficult challenges, including competition with a competitor already in the market, in order to deliver a set of values it believed would be more appealing to both the entertainment industry and to consumers. Taking extra time and money to incorporate sources of value in innovative projects has two major benefits:

- It provides additional reasons for customers to prefer your product over those of competitors.

- It ensures that competitors will have greater difficulty in exploiting your omissions. In traditional product development, success is measured in terms of time and cost to market.

Time to Market

In this model, the project manager can trade cost and time in order to achieve the predetermined results. If changes to those results are dictated by changes in the environment, they may either be ignored or the project may be rethought.

The future is not deterministic. “The relationship between cause and effect gets lost in the details of what actually happens.” On our dynamic planet, reality changes from moment to moment. Markets change. Goals change. The measure of success changes. In this dynamic world, a more adequate measure of project success is time to profit. This measure incorporates both the investment period and the recovery period.

Time to Profit

This model opens several new doors to the project manager. Adding additional sources of value to the scope of the project may extend the time/cost to market or implementation of internal, cost saving projects. It may, however, shorten the time to profit/savings. In the time to market approach, project managers manage project cost; in the time to profit approach, [project cash flow is the management object.]

Research done by the Product Development and Management Association in North America indicates that only one development effort in eight is successful in achieving its return on investment objectives. This means that project management should be considered as successful not only if the project reaches its target but also if the unsuccessful project is terminated as soon as its potential failure becomes probable. The time to market project management approach looks ahead only to the product delivery date. Project managers are not expected to be concerned with product profits. In the time to profit project management model, the project management team is motivated to achieve business goals. Project scope includes future sales, and the project management team will monitor the likelihood that project business results will be achieved. The traditional project management approach suggests treating each project life cycle phase as an independent project. Project outcome goals are considered only at the time when phases begun and are not revisited as phase execution garners new information. In the time to profit approach, project managers consider the probability of reaching project business goals continuously, because all project management decisions must be based on future profit criteria.

Innovation and Risk (Management)

Innovations mean a lot of uncertainties and risks. Organizations that are involved in innovation management choose to accept a high level of risk. They are successful not because they get lucky, but because they actively manage the risks they take. Threats, opportunities, and uncertainty are assessed and thoroughly planned. Research carried out among customers of Spider Management Technologies, showed that projects that were planned based on the most probable estimates of the project parameters had low probability of being on time and within budget. In our experiments with real projects, the probabilities of achieving project performance goals based on most probable estimates never exceeded 38% and usually were even lower. Therefore, it is natural that most projects are late and over budget because they were poorly planned.

Active Risk Management (ARM) deals with future uncertainties that may be either opportunities or threats. To use ARM effectively, project managers ask a series of questions, first focused on opportunities and then focused on threats. The ARM questions are:

For Opportunities

- What events might occur that would speed our time to profit?

- Can we do anything to increase the likelihood of their occurrence?

- What would we do if they did occur?

- Will anything alert us that they are about to occur?

- What must we do before they occur if we are to take advantage of them?

For Threats

- What events might occur that would delay our time to profit?

- Can we do anything to decrease the likelihood of them occurring?

- What would we do if they did occur?

- Will anything warn us that they are about to occur?

- What must we do before they occur if we are to avoid the damage?

It is usual for most future events to be treated as both opportunities and threats. For example, in a new product development project, it is always possible for a competitor to get a product to market before us, particularly if we are using the time to profit strategy. While this event brings the threat that our competitor will gather many of the potential customers before we have a competing product ready to sell, it also offers substantial opportunity. We can now study what our competitor has done in detail, identify its strengths and weaknesses, and modify our own project plan to ensure we have strengths to match our competitor while also ensuring that we are strong where organizational competitors might be weak.

Core components to drive sustainable innovation.

Any successful organization and its associated Architecture capability needs to ensure it fosters and can govern managed innovation, below highlights the typical innovation strategies that could and have been adopted previously.

Discovery

- Use an Open Innovation approach with processes and toolset in place initial Discovery cycle

Research & Design

- Put in place an Innovation funnel to search, select, refine, enrich the concepts identified during the Discovery phase

Prototype & Seed

- Build rapid prototypes and move to seeding outputs and lessons learned used to refine the next iteration of the Innovation process: making this approach iterative

Context and Tools

ITABoK 3.0 by ITABoK 3.0 is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://itabok.iasaglobal.org/itabok3_0/.